The Culmination

May 4, 2009

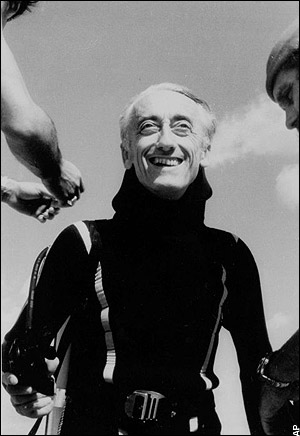

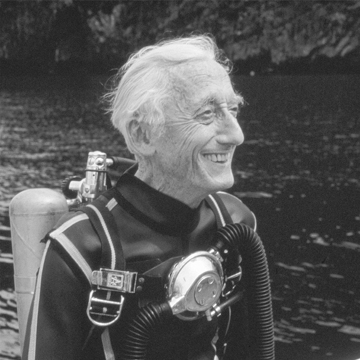

Much to our relief and dismay, Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s body was retrieved from an underground area near New York City Water Tunnel No. 3. He attempted to do research on the sewergator, his most recent topic of investigation, alone and at night. He crawled through several tunnels until he found what he was looking for. We have included in this blog all of his research relating to this topic, as we are all certain that this would have been his wish.

His last writing on the sewergator is as follows:

“I have just recently interviewed a member of the machine crew from Tunnel No. 3. According to the website, the tunnel

‘is one of the most complex and intricate engineering projects in the world. Constructed by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, the tunnel will eventually span 60 miles and is expected to be complete by 2020.

The size and length of the tunnel, its sophisticated control system, the placement of its valves in special chambers, and the depth of excavation, represent state-of-the-art technology. While City Tunnel No. 3 will not replace City Tunnels No. 1 and No. 2, it will enhance and improve the adequacy and dependability of the water supply system and improve service and pressure to outlying areas of the city. It will also allow the DEP to inspect and repair City Tunnels Nos. 1 and 2 for the first time since they were activated.’ (http://www.water-technology.net/projects/new_york/)

There have apparently been some sightings by the crew working on the tunnel. I must see to it that the alligator doesn’t evade me this time.

In order to insure this, I will go alone with my recording equipment. It is impossible to move about unheard in the depths with a crew of three men swishing about. One man is much quieter. There will also be less light, as I will be the only one carrying a light source, as opposed to three men. I can crawl into smaller spaces because of this as well.

It is intuitive that I should want to find this gator, gators, or community of alligators that exist below detection. It would not only be the answer to a long-standing myth, but it would testify to the resilience of nature herself. Persecuted and demonized, alligators are often relegated to the outskirts. And here, this is literally the case. They are unacknowledged citizens of the urban center. I intend to find them.”

These were the last words written by Captain Cousteau. He carried his recording equipment with him, and we have here posted the outcome of Captain Cousteau’s tireless research into the natural world.

Please see the video (below) for the last footage taken by Cousteau prior to his death…

This blog is in memory of Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s work and his lifelong dedication to the investigation of our world.

The Crew

My work tells stories. I invent situations, cities and worlds. These compositions include memories, associations of words, ideas, observations and thoughts that unfold in improbable juxtapositions. These invented worlds have their own logic and patterns. Images are conveyed through words, whether automatic writing or premeditated scenes. My creative inspiration comes from a text, a poem, the news or from a philosophical concept that can be reduced to a mere title. I research collective memories and myths, questioning the notions of identity and belonging. For each theme, I explore various narratives: one story leads to the next, and the creation process weaves different layers of our relations to the world.

My silhouettes are a language I have developed over the years; my point of view is both detailed and monumental. Cutting from a single piece of material, the profusion of individual stories creates a coherent universe. In my artist books and public art, where I play with full and empty shapes, everything must fall in place: one’s place in the world, one’s place in the city, one’s place in his or her body. In my graphic style, windows are used not to see out but in, placing the spectator in an outsider/insider situation. Shadows, reminiscent of film noir and voyeurism, leaves room for multiple interpretations.

–

Artist Website: http://beatricecoron.com/

–

About Arts for Transit:

As you travel through the Metropolitan Transportation Authority network, you experience a first-rate art museum with works created in mosaic, terra cotta, bronze, glass and mixed-media sculpture.

The founders of the New York City subway believed that every design element in the system should show respect for our customers and enhance the experience of travel. Language was added to contracts that required the highest quality materials and craftsmanship. This led to the extensive use of ceramic tile, terra cotta and mosaics as decorative elements. As the century-old transportation network is restored and renewed, these decorative elements of the past are preserved and protected as contemporary art and design are introduced.

In conjunction with a massive rehabilitation program launched in the 1980’s, MTA Arts for Transit was created to oversee the selection of artists and installation of permanent artworks in subway and commuter rail stations. The program encompasses Music Under New York, a Transit Poster Program and the Lightbox Project, a series of photography exhibits.

We invite you to discover and enjoy this diverse and beautiful collection of commissioned public artwork installed throughout the subway and commuter rail stations of the MTA.

History of Arts for Transit:

Arts for Transit was created nearly 25 years ago when the subway system was beginning to reverse years of decline through an ambitious capital improvement program. The MTA’s leadership determined that original, engaging and integrated artworks should be part of the rehabilitation and construction process and civic leaders and arts professionals agreed, lending their prestige and support to various committees that developed the policies and procedures to include art as an integral part of the rebuilding effort. The program’s establishment occurred as both the historic preservation and public art movements began to influence public policy and as cities nationwide began their own rebuilding programs. Arts for Transit’s work continues to flourish in today’s environment, as the use of mass transit continues to grow, and more stations are rehabilitated, which in turn increases the presence of art in MTA stations.

The unique set of conditions within the subway system calls for durable materials that can easily be maintained. As a result, Arts for Transit projects are created in ceramic tile and mosaic and other media, such as bronze or glass. The Arts for Transit program also plays an important role in the physical restoration and attention to design elements within the stations; this includes not only artwork, but gates, fare vending machines and even the design of subway cars.

The program remains faithful to the founders’ credo that the subway should be an inviting and pleasant environment, geared to the user, with the highest levels of design and materials. New works of art follow these principles, as Arts for Transit upholds the high standards initiated over 100 years ago.

Art Card Program:

The Art Card Program was initiated in 1999. The Program provides opportunities for illustrators, print, and other visual artists to create transit-themed artwork for display within new subway cars. Subway riders have the opportunity to enjoy colorful imagery as a source of thought and inspiration while traveling through the system. The Program provides illustrators and other artists the opportunity to reach a broader public, while expressing the people, places, and purpose of the transit network with visual appeal and variety.

A variety of Posters and Art Cards are available for purchase at the New York Transit Museum stores.

MTA Arts for Transit: http://www.mta.info/mta/aft/

City Hall Revealed

May 3, 2009

The Nest

The City Hall subway station was officially closed and abandoned on December 31, 1945. Tours were still offered until quite recently, and now the station has fallen into complete disrepair. Still, the occasional MTA Inspection worker is sent to investigate its conditions. Such is the character of my next interview and thus my next descent into the underground.

City Hall is close to the Canal Street/Chinatown area, and so it seemed a logical location for my next investigation. The street entrances to the station are now sealed, so we entered through a sewer shaft that actually led us to the station. As with the previous descent, I brought two crewmembers with me and left the rest inside the station, and above ground, to monitor our progress and standing.

Diving gear was unnecessary for this attempt because we were going to walk through the abandoned subway line. We did, however, wear long rubber suits, helmets, and the same monitoring and recording devices as before.

This line was not as warm as the sewers had been, but the air was still stagnant and smelled of the refuse floating immediately below and beside the old tracks. We trudged along in the dim light until we saw a large crack in the wall, from which rats were openly and unabashedly scurrying. We decided to go in.Clutching to the wall for guidance, we eventually were led into a larger corridor that seemed to be an abandoned construction site. Water was everywhere, and it floated above our ankles. I later found out that this was an integral portion of the station’s history:

“City Hall Station opened along with the rest of the Interborough’s first subway line on October 27, 1904. It was immediately clear that expansion of the subway system would be necessary and additional lines were built. But ever-increasing ridership eventually required the Interborough’s five-car local stations to be lengthened to accommodate longer trains, and so the IRT underwent an extensive program of station lengthening in the 1940s and early 1950s.

City Hall, due to its architecture and its being situated on a tight curve, was deemed impractical for lengthening. The new longer trains had center doors on each car, and at City Hall’s tight curve, it was dangerous to open them. It was decided to abandon the station in favor of the nearby Brooklyn Bridge station…” (http://www.nycsubway.org/perl/stations?5:979)

Clearly an attempt had been made to expand the station into the surrounding strata. After this had been deemed impossible the site was abandoned altogether, and is now almost completely forgotten by its human progenitors. Because there are only small cracks for air to flow, this site was quite warmer and gave me a distinct feeling of suffocation. Despite this, the plants and animals had not forgotten, nor had they hesitated to take advantage of such a fortuitous situation. They had formed their homes in the rubble, and had appreciated its protected nature. They flourished in this environment. If we were to find an alligator nest or even an alligator themselves, this would have been an ideal location.

And so we did. Tucked in a small corner of the rock lay an alligator’s nest devoid of eggs. Had this been the former home of the egg we found in the sewer? We took some samples and, after searching for a bit more and finding nothing, ascended back to the surface.

I was becoming restless. How could these alligators evade detection so well? Obviously, there were alligators living below the streets of New York. I had only found bare traces of this, though, and was eager to find the alligators themselves. Perhaps the means to avoid detection had been one of their urban adaptations?

Interview #4 – Unnamed MTA Employee

May 2, 2009

Residence: Not Provided

Incident Location: City Hall Subway Station (Not In Use), Opened 10/27/1904, Closed 12/31/1945

Age: Not Provided

Gender: Male

Occupation: MTA Employee

Injury or Fatality: Yes

Other Witnesses: Unknown

MTA Employee did not provide name. For further information see police report.

BEGIN RECORDING

Captain Cousteau: Hello! Thank you for meeting with me. Please recount your sewergator encounter with as much detail as possible…

MTA Employee: Located under City Hall Park is the world’s most beautiful subway station! It is located at the south edge of the loop that turns Lexington Avenue Interborough Rapid Transit subway (#6) around to the south of the Brooklyn Bridge station. It can be seen, if your conductor allows, by staying on the #6 local after the end of the line riding southbound, and looping around to enter the Brooklyn Bridge station northbound.

At the 1900 groundbreaking, this station was designed to be the showpiece of the new subway. Unusually elegant in architectural style, it is unique among the original New York subway stations. The platform and mezzanine feature Guastavino arches and skylights, colored glass tilework, and brass chandeliers. The curved platform is about 400 feet long (the length of a five car train minus the front and rear doors as was the IRT’s standard design for a local station when it was constructed). In the center of the platform is an archway over stairs leading to the mezzanine. On each side of the stairway, there is a glass tile “City Hall” sign, and a third is on the archway above the stairs. No other signs like these were used in the other IRT stations of the era. The lettering is quite unique in deep blue and tan glass tiling.

Twice a month, I am assigned to a brief City Hall station inspection. I always disregard the brevity, preferring to linger in this unused, but beautiful space for as long as possible.

I had arrived on time and began my inspection as I always had. I quickly picked up any garbage that had blown down the tracks or been carried in by pests. I checked the rodenticide delivery system, to ensure that the station was fighting the constant threat of rat overpopulation. Next, I check the light fixtures to ensure that everything was in proper working order.

I saw him as I moved my stepladder to the next fixture. His body was between the side rail and the platform, piled in a heap like dirty laundry. He was unrecognizable. Hardly human. Most of his skin and muscle tissue had been removed. I couldn’t tell you what color hair he’d had. A black tee-shirt and a pair of jeans were wrapped in the remains. The body was approximately 6 feet tall. I immediately called the police and my dispatcher. They both asked me to stay and supervise the body until they arrived.

I placed my step ladder at the edge of the platform within view of the body. He appeared to be a white male. I couldn’t tell you how old he was. I spotted his footwear and hypothesized that he’d broken in and was electrocuted by the active third rail. People were always breaking into the City Hall station. Either that-or he was homeless and sought shelter here. We occasionally find the bodies of “mole” people who are not actually related to moles in anyway, but are given that name because live in a secret society in the subway infrastructure and rarely come up for air. Sometimes these “mole” people drink too much and fall asleep on the tracks only to be run over when the next train rolls through. We’ve found “mole” people who have been rejected by their underground society and accordingly murdered.

I didn’t know this man’s story, but I knew there was something odd about this body. In my ten years with the MTA, I’d seen three bodies on the tracks. This body seemed damaged in a way that passing trains and rodents could not have caused. Large chunks of the body were missing. They were ripped from his body and could not be located.

That’s when I saw it. A small white tooth, located in the shoulder. I leaned closer, peering over the platform for a closer view. Without thinking, I reached down and pulled the tooth from the man’s shoulder.

After realizing that I might have impeded the investigation and incriminated myself by leaving fingerprints on the tooth, I quickly shuffled the item into my pocket. I gave my statement to the NYPD (casually leaving out the part about a tooth).

At first, I wasn’t sure the tooth belonged to an alligator. I completed research online and after doing a Google image search felt certain that this item had been in the mouth of a gator. Samples of alligator teeth could be found as lucky charms and jewelry, available for purchase online.

After that day I asked to be removed from the City Hall shift. The body was never identified.

END OF INTERVIEW

Alligator Tooth:

Photos of Incident Location:

Collect Pond and the Modern City

I have conducted several more interviews, but only one seems to lead in any constructive direction—a father and daughter who lost a beloved pet to the Chinatown sewer system. This area has an incredibly rich history which is both forever forgotten and forever memorialized by the modern sewer system of New York:

“Before the Five Points, there was a little part of Manhattan called the Collect Pond. This underground spring-fed lake was a major source of fresh water for the people of New York, but by the late 1700s, it grew too polluted for use due to the many tanneries, breweries clustered near it, and the use of the pond as a dumping ground by others. The city began draining the Collect starting around 1802 by backfilling it with construction debris, and whatever garbage they could find.

There was a problem though…. people soon realized all that water had nowhere to go as the surrounding low-lying area was already marshland, and occasionally flooded. Because of health concerns (malaria), the city drafted a plan in 1807 to build a canal to drain all the water from the surrounding area, and whatever remained of the pond. The Collect Pond was finally drained by 1811. The recovered waterlogged land, was used to build a massive prison called the Tombs in 1838. The canal itself remained until 1821 when it was covered over, and used as an underground sewer.

Yes, there really was a canal at Canal Street. It was built in 1808 to drain the collect pond and the surrounding area of water. In 1821, the canal had gotten to the point of smelling so bad that the city covered it up and turned it into an underground sewer” (http://www.nychinatown.org/history/1800s.html)

Today, a portion of the original Collect Pond is a park (entitled appropriately Collect Park). Canal street is still the location of a major sewer line running through Chinatown. This is where I had to continue my search.

The Aqua Lung

Due to the unusual conditions of this expedition, I did not want to have a full crew at hand. The Canal street tunnel is large, but entering into smaller tunnels it would be difficult to stay together. Because of this, I chose two other men to accompany me below the surface, and the rest of my crew stayed above ground monitoring our breathing, heart rate, and other vitals. We did not know how much liquid would be below and if we would be completely submerged, so we suited up in Aqua Lungs to begin this journey. Essentially, the Aqua Lung allows us to breathe without connecting to an air source above water, though we still remained connected to each other and the outside world via our radio system (which was inside of our headpieces), and our video equipment, which we attached to the outside of our suits.

We entered the sewers at midnight on a warm summers’ evening at the intersection of Canal Street and Broadway. Alligators are most active at night, as I mentioned before, and they are also most active between 82 and 92 degrees Fahrenheit. I want to see these amazing creatures in movement, in life. I have no desire to remove them, as they have become just as integral to the city wildlife as any other, including the common sewer rat.

The two crewmen and I made were lowered into the bowels of the city by those who would stay above. The burst of stale, gaseous air hit us immediately. It was warmer than one would think—the heat from the drifting liquid and from the enclosure itself was incredible. The interior of the sewer was dark but light could be seen emitting from far off in the distance, and we immediately turned on the few lights that we had brought for the occasion. We waded in the waist-deep refuse seeing little rats scuttle by in the crevices of the tunnel. Of course, we were extremely cautious and quiet, making sure to view all around us. We did not want to have any hungry alligator sneaking up on us.

Unlike the deep ocean, the deep sewer is a reminder of the human life above. The garbage ran around our bodies and little bits of the city’s life seemed to come to light: what people had ate, what they read, where they had gone to the cinema. It became clear that an alligator would have absolutely no trouble surviving in these conditions. It was humid and balmy, there was plenty of food both from humans and from the rats and other creatures, and the water was, polluted, yes, but also shallow and warm.

After a few hours, we prepared to ascend to our fellows.

We did not find an alligator.

But we did find something even more precious—an alligator egg. It was completely in tact, though apparently had abandoned at some point before we found it as we could find no other eggs and no visible nest. It could have fallen or been knocked out of the nest and drifted in the sewage to the location where it was found by us.

We were getting very close to a major breakthrough.

The Sewergator Egg

Interview #3 – Richard and Madison Wake

April 30, 2009

Residence: Chinatown, Manhattan

Incident Location: Chinatown, Manhattan

Age: 8 and 36

Gender: Female and Male

Injury or Fatality: No

Other Witnesses: Yes – Wife and Mother

BEGIN RECORDING

Captain Cousteau: Hello Richard and Madison! Thank you for meeting with me. Please recount your sewergator encounter with as much detail as possible…

Richard Wake: Madison should begin. The alligator was her pet.

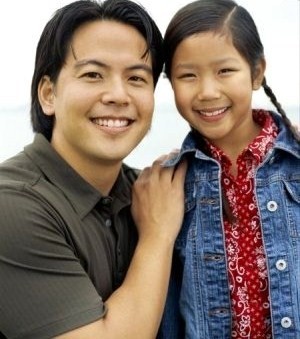

Turning and addressing Madison, an 8 year old girl with pigtails.

Madison, honey, could you tell Mr. Cousteau about your pet?

Madison is distracted by the recording equipment and does not answer.

Madison, this man would like to talk to you.

Madison Wake: Yes daddy?

Madison shyly agrees to discuss her pet. She refuses to make eye contact with Captain Cousteau and climbs onto her father’s lap.

Madison pats her father on the face. She retracts her hand, surprised by the feeling of his whiskers against her palm. She frowns.

You want to talk about Albert?

Richard Wake: Yes, Maddy, tell Mr. Cousteau about Albert, your alligator.

Madison Wake: Albert was my pet. I kept him in a terrr-air-e-um on the desk in my room next to my bed. Daddy built him a water pool. And I found sticks and bark and rocks and dirt in the park for him to live on. Then we went to the pet store and purchased a heating lamp.

Richard Wake: Tell the Captain where the alligator came from.

Madison Wake: Madison looks to her father for direction and then looks away.

Suddenly her eyes light up and she leans closer to the recording device.

Grandpa Wake! I got him with Grandpa Wake.

Richard Wake: Let me explain. Madison went to Florida last summer to visit her grandfather. They went fishing on the boardwalk and Madison caught Albert!

Madison Wake: I reeled him in!

Richard Wake: My father purchased a terrarium that mimicked the natural environment the animal would live in. The cage had a jungle motif. The alligator and terrarium arrived by mail just after Madison returned from vacation.

Madison crawls off her father’s lap and walks to the door.

Go see mommy. She’s in the lobby.

Madison nodded okay and ran out the door. She made heavy footsteps that the recording device picked up.

Richard Wake: Sighs and brings his hand to his forehead.

I’m sorry… now I can tell you what really happened…

The city warden service took possession of the alligator because we did not have a permit to possess the reptile. We were issued a summons for keeping wildlife in captivity and importing and receiving wildlife without a permit. I appeared before the Supreme Court on March 4th of last year and receive a fine of $300. The warden received a tip about the alligator from a “confidential informant” who saw pictures of it on the Internet. We posted photos of Maddy and Albert on Flickr for my father to view. The photos were of Albert, with tape around his mouth, sitting at the table for Madison’s birthday celebration. We were all gathered around the table singing and the gator looked happy enough. He was part of the family then.

A zoologist accompanied the warden. When they took the gator out to their truck, they cut the tape that secured the Albert’s mouth and the gator began to thrash wildly. The zoologist wanted to check the integrity of the gator’s teeth. The beast bucked wildly and the zoologist lost the gator down a storm drain next to the curb.

The police arrived and removed the drain cover. City workers crawled into the drain after the alligator, but Albert was gone. They never found him.

Had the alligator been safely transported to the animal rescue facility in Brooklyn that has a permit to possess exotic animals, we could have visited and Madison could have said goodbye. As it is, it seemed best to tell Maddy that God had taken Albert to heaven.

END OF INTERVIEW

Photos of Incident Location:

Permit Information:

An importation permit is $27, and a possession permit for propagators and general wildlife or fish also is $27. An exhibitor permit is $147.

An individual seeking a permit would call the department about their interest to import and possess an exotic, non-native animal. A discussion would take place as to what the intended use is of the animal. Once a prospective classification is determined, the applicant would need to submit all of the required information asked on the application as well as a veterinarian inspection. If an animal is going to be possessed, the caging facilities also would need to be inspected.

Photo of Albert:

Photo of Richard and Madison Wake:

Progress and A Decision Made

April 29, 2009

The East River... an alligator throughway?

My second interview with Rusty proved fruitful. His testimony confirmed my suspicions—there was and is several generations of gater lurking in the waters of the metropolis. What disturbs me is the water quality of the East River, especially at the latter half of the 19th century. It is quite polluted, and is actually dangerous to swim in, though now in 2009 it is much cleaner than ever before. What type of adaptations must these alligators have to be able to survive in such a habitat?

The alligator that injured Chester may still be alive, but Chester has long since passed. I could not investigate his tail to see if the bite marks are consistent with an alligator’s jaw and teeth. My supposition is that it must have been a relatively small alligator; a larger creature would have devoured Chester. Perhaps a more appropriate term is maim. You see, alligators perform what is known as a “death roll” on order to eat their prey. They tightly grip the prey by its body and use their powerful tails to swing that body around until bits of flesh are removed. Only a relatively small gator, even a baby, would have been able to remove a cat’s tail and leave the rest unharmed. The water in that area though moves quite rapidly, at about a speed of four knots. The alligator must be small but an incredibly strong swimmer.

The East River, where Rusty believes the alligator to have lived, connects Upper New York Bay on the south to Long Island Sound on the north. These gators would have a range of habitat then, from the boroughs of the city to Long Island. I decided that Manhattan would be the best center for this type of habitat for several reasons. Namely, the island is actually centrally located, has an intricate network of underground systems including the sewer, the subway, and the tunnels to and from the city that are tightly woven and interconnected, and most importantly, Manhattan is perhaps the only location where such a peripheral population could have gone unnoticed for almost a century.

I decided not to physically investigate the East River. It is too dangerous for swimmers to enter its waters (including scuba divers) because of the levels of toxicity and because of the speedy current. As an alternative, my crew prepared to enter the urban subterranean depths in search of the sewergater.

First Dive

April 28, 2009

Sewergator?

Clearly Ms. Coventry and her lawyer Louis had seen something unusual—or had they? The dog could have simply gotten caught in some underwater muck and drowned. Typically, alligators live in the south eastern portion of the United States, in the lagoons and swamps. They are usually between 6 and 14 feet. Crocodiles, on the other hand, are not native to the US. It is for this reason that I knew we were searching for an alligator. I still had many questions though: was this one isolated case? Or was there a colony of alligators just below the city’s surface? Smaller alligators tend to live in large groups. Unfortunately, neither Ms. Coventry nor her lawyer were able to see how large the animal was because it was partly submerged.

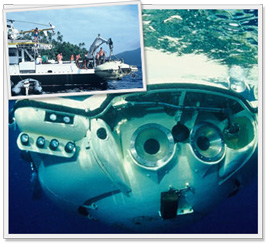

The Diving Saucer

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir, located between 86th and 96th streets, can certainly sustain a population of large reptiles. According to Central Park’s official website, the reservoir, “covers a full one eight of the park’s surface. The 106-acre water body is 40 feet deep and holds over a billion gallons of water,” (http://www.centralpark.com/pages/attractions/reservoir.html). Until 1991, the reservoir was an integral portion of the fresh water supply in the city. Since then though, it has been largely converted into an aesthetic attraction and this has allowed the park’s wildlife to live there in peace. Though not able to utilize Calypso, my ship, in the reservoir, I decided to investigate this incident with my crew using the Diving Saucer. The Saucer can dive as far as 350 meters (equal to approximately 1,150 feet) and can stay underwater for up to five hours (http://www.cousteau.org/technology/diving-saucer). This tool would be perfectly suited to an exploration of the vast reservoir.

Taking a member of my crew with me, the Diving Saucer was transported to New York and prepared for the dive ahead. Alligators are nocturnal, and so I thought that we would descend in the manner of an alligator, at night, in order to catch a glimpse. When we finally descended beneath the dark, still waters of the reservoir, I kept the Diving Saucer’s lights dimmed. I did not want to frighten any creatures, especially this alligator. We viewed the magnificent wildlife that calls the reservoir their home, but still we did not see any sign of the alligator.

As it does every morning, the sun began to rise at about 5:30. My crew members and I had scanned the waters from above and below the surface, but we had not seen an alligator or, for that matter, any unusual or large creature. Though beautiful and majestic, the small fish and birds native to the reservoir were not what we had come in search for. I felt disappointed, but I was not discouraged. We had set out two weeks after the incident relayed by Ms. Coventry. By now, the alligator could have easily wandered over land to another body of water in the park, or could have entered one of the many abandoned sewer tunnels leading into the heart of the city.

I needed more interviews, more information. The reports of a “sewergator” were numerous, but many dated back many, many years. The alligator of the 1935 reports would not be alive today. If the reports have any truth to them, that alligator(s) would have left descendants; Pollock’s could have been one of those descendants. In the wild, alligators can live from 35 to 50 years and they reach sexual maturity at about 10 to 12 years of age. That means that there is a possibility that seven generations of gators have been born since the original sewergater, five of which could still be swimming in the depths, and every generation increasingly adapted to their adopted environment. I absolutely had to find this hidden habitat.

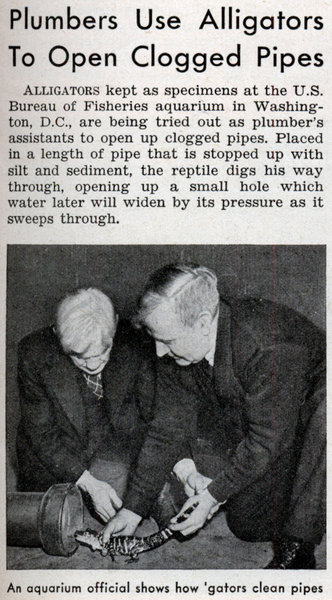

Plumbers Use Alligators To Open Clogged Pipes

April 24, 2009

“Alligators kept as specimens at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries aquarium in Washington, D.C, are being tried out as plumber’s assistants to open up clogged pipes. Placed in a length of pipe that is stopped up with silt and sediment, the reptile digs his way through, opening up a small hole which water later will widen by its pressure as it sweeps through.”

From: http://blog.modernmechanix.com/2007/04/04/plumbers-use-alligators-to-open-clogged-pipes/

Live ‘Gator’ Captured in Brooklyn

April 24, 2009

Wednesday November 29, 2006 – “It was found behind an apartment building in Brooklyn, not in the sewers of Manhattan; it isn’t particularly big (under two feet long, police say); nor is it even, strictly speaking, an alligator (it’s a caiman). Still, press reports on yesterday’s discovery of an abandoned saurian are likening it to the age-old urban legend about discarded pet alligators thriving in the New York City sewer system. Some say the creatures grow to monstrous size and turn white due to the lack of sunlight.

The urban legend is false, of course, but “gator” sightings do occur with some regularity in New York and environs, odd as it seems. The last such incident happened five years ago, when a specimen of similar size — dubbed “Damon the Caiman” by city officials — was captured in Central Park. Though illegal in the city, caimans can be bought on the Internet and are sometimes kept as pets, only to be abandoned when they outgrow their welcome.”

From David Emery’s Urban Legend Blog (urbanlegend.about.com)

Alligator vs. Caiman - Caimans are the most common alligator pets. They are a so called miniature alligator.